36

36

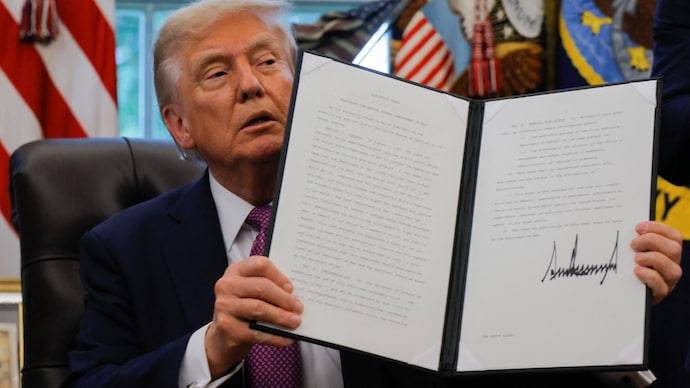

Since Donald Trump’s return to the White House, the world has witnessed a rapid escalation of U.S. military activity abroad. The United States—long self-branded as a champion of human rights and peace—has, in Trump’s second term, increasingly transformed into a central engine of war and instability across multiple regions.

Trump has authorized a series of military operations ranging from the unprecedented use of bunker-buster bombs against Iran’s most fortified nuclear facilities to an ongoing “counter-narcotics” campaign off the coast of Venezuela.

This comes despite Trump’s own words at his inauguration, when he declared:

“We will measure our success not only by the battles we win, but also by the wars we end—and perhaps most importantly, the wars we never enter.”

Yet data compiled by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) and cited by Military Times tells a different story. Since taking office on January 20, 2025, Trump has overseen at least 626 airstrikes. Under various questionable pretexts—such as counterterrorism and drug trafficking—the United States has attacked countries including Somalia, Iraq, Yemen, Iran, Syria, Nigeria, and most recently, Venezuela.

Somalia – February 1, 2025

Iraq – March 13, 2025

Yemen – March 15 to May 6, 2025

Iran – June 22, 2025

Syria – December 19, 2025

Nigeria – December 25, 2025

Venezuela – December 2025 and ongoing

This raises a critical question: what did Trump say about U.S. military action abroad before his second term—and what is he doing now?

For years, Trump portrayed himself as a critic of “endless wars,” condemning U.S. interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan while promising an “America First” foreign policy. Yet his second term reveals a pattern of selective military force, consistently framed as defensive or counterterrorism operations. Notably, the attack on Venezuela has gone so far as to redefine the very meaning of deterrence and peace. Trump—once a leading advocate of “America First”—now dismisses that very doctrine and its supporters as passive.

In the case of Venezuela, the U.S. administration has attempted to justify its actions as “limited operations,” “counter-narcotics missions,” or “criminal arrests,” deliberately avoiding the need for congressional authorization. Critics argue that because Venezuela did not attack the United States, these actions exceed presidential authority and constitute violations of both domestic and international law.

Democratic lawmakers, along with several Republicans, have stated that the president launched these operations without congressional approval and that Congress must intervene. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer declared:

“Since the founding of our republic, the Constitution has clearly and exclusively vested one power in Congress: the power to declare war. Let us be clear—Congress has not declared war on Venezuela… The American people do not want to be dragged into another endless and pointless war.”

A member of the Senate Armed Services Committee and a senior member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee similarly warned:

“We should not risk the lives of our service members in military operations inside Venezuela without robust debate in Congress. That is precisely why the power to declare war was given to Congress—not the president.”

Human rights organizations and UN experts have also stressed that counter-narcotics operations are law enforcement matters, not armed conflicts, and must be conducted under strict human rights standards—not the looser rules of international humanitarian law. The current U.S.

approach, which prioritizes military force over judicial processes, undermines the rule of law and sets a dangerous precedent for the use of force in similar contexts.

Under the U.S. Constitution, the authority to declare war lies with Congress (Article I), while the president serves as commander-in-chief (Article II). The War Powers Resolution of 1973 requires the president to notify Congress within 48 hours of initiating hostilities and to terminate them within 60 to 90 days unless Congress authorizes further action. The Venezuela campaign raises serious constitutional concerns: there has been no declaration of war, no specific authorization for the use of force, and no credible claim of an imminent armed attack against the United States that would justify unilateral executive action.

Legal scholars argue that sustained military strikes and the expanded naval presence exceed the president’s lawful authority and that Congress has failed in its duty to authorize or restrain the conflict. While Congress has twice rejected resolutions aimed at limiting presidential powers in Venezuela, it has not passed a new Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), leaving the operation in a constitutionally precarious state.

Historically, U.S. presidents—particularly since the 1950s—have frequently initiated military operations without formal declarations of war. Congress has often issued broad, preemptive authorizations (such as those tied to the “war on terror”) or avoided direct involvement altogether. The War Powers Act itself contains significant loopholes and, in practice, offers limited restraint.

Trump’s actions in Venezuela thus fit squarely within this long-standing pattern: a president invoking executive authority to justify military force while Congress either cannot—or will not—play a decisive role in formal authorization. The criticism voiced by certain senators and representatives amounts largely to political theater.

In reality, successive U.S. presidents have demonstrated that they will pursue their interests by any means necessary. International organizations and legal institutions have proven powerless against Washington’s reliance on brute force. This behavior is not unique to Trump’s aggressive policies; it has been a recurring feature of U.S. governance across administrations.

Driven by his desire to present himself as the most powerful man in the world, Trump’s actions have become increasingly unpredictable and uncontrollable. He pursues his objectives with near-manic determination—and the cost of his militarism is ultimately paid by the American people themselves.

Translated by Ashraf Hemmati from the original Persian article written by Hakimeh Zaeem-Bashi

https://wps.news/2026/01/03/congress/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Comment

Post a comment for this article